As the new school year has begun, public schools across the United States face a common problem — rising absence rate, which was worsened by the pandemic and shows no sign of abating.

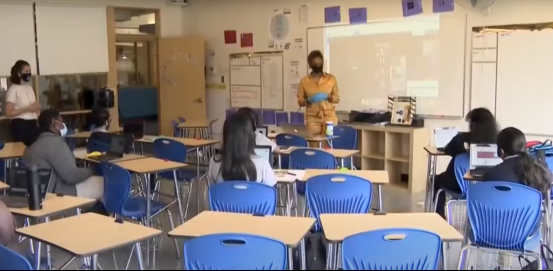

From West Coast to East Coast, from urban to rural districts, public schools are struggling to bring students back to classrooms. Many local news outlets said this week that some schools have to get creative to combat chronic absenteeism.

Chronic absenteeism means missing 10 percent or more of a school year. For students on a typical 180-day school calendar, this totals about one month of missed school.

In Bakersfield, California, McKinley Elementary School held a “Walk to School” event on Friday, inviting parents and community leaders to walk students into school. The school said the goal was to address chronic absence. Last year, 45 percent of the school’s students were chronically absent.

In Baltimore, Maryland, Mayor Brandon Scott launched a friendly competition between schools this week to tackle the same absence problem. The mayor planned to hold a special event at the end of the school year, where he would award trophies and certificates to schools that have achieved significant progress on attendance rate.

ABSENTEEISM WORSENED BY PANDEMIC

The rate of chronic absenteeism among U.S. public school students grew substantially as students returned to in-person instruction from the COVID-19 pandemic.

A new national analysis, based on data from 40 states and Washington, D.C., found that since the pandemic the number of students who were chronically absent nearly doubled to about 13.6 million.

“Specifically, between the 2018-19 and 2021-22 school years, the share of students chronically absent grew by 13.5 percentage points — a 91-percent increase that implies an additional 6.5 million students are now chronically absent,” said the study by Stanford University education professor Thomas Dee.

The study, published in August on OSF Preprints, showed that absences worsened in every state. In seven states, the rate of chronically absent students doubled for the 2021-22 school year from the 2018-19 year.

For the past 2022-23 school year, Connecticut has reported continuing high absence rates. The state’s education department released the 2022-23 attendance and student assessment data on Monday, which showed chronic absenteeism remains nearly double pre-pandemic rates.

More than 100,000, or 20 percent, of students across the state were still missing at least 18 days of school throughout the year, according to the report. Prior to the pandemic, about 10.4 percent of students were chronically absent.

In California, the rate of chronically absent students rose from 12.1 percent in 2018-19 to 30 percent in 2021-22, according to Dee’s study, with the highest chronic absenteeism rate of 35.7 percent in rural districts.

The analysis showed that 1.77 million students across California missed at least 20 days of school through 2021-22 year. The state’s attendance data for 2022-23 is not yet available.

It also found that rural districts have seen the sharpest increases in chronic absenteeism and that the problem has been especially acute among Native American, Black and Latino students.

CAUSES UNCLEAR

Educators tried to find out what caused the rising absence rate and found there were a variety of factors.

Connecticut Education Department had surveyed over 5,000 families regarding absences. Responding families said illness was a leading factor for keeping their students at home, followed by mental health and family obligations.

In Detroit Public Schools Community District, 77 percent of students were chronically absent during the 2021-22 school year. Experts said the reasons were largely rooted in the economic challenges — transportation hurdles, health problems, family and housing instability.

The exact causes for the sharp spike in absenteeism were unclear, Dee said in his study, adding there’s no evidence of linkage with sickness, enrollment loss, or COVID-related policies, such as mask mandates.

“This suggests the sharp rise in chronic absenteeism reflects other important barriers to learning (e.g., declining youth mental health, academic disengagement) that merit further scrutiny and policy responses,” said Dee.